Once upon a time in the scorching region of the Sahara, a fresh Tuareg son named Iyad company Ghali watched his father death in a doomed revolution. The year was 1963, and that pain may leave a lasting impression. Like some” sons of ‘ 63″, Ghali grew up suspicious of Bamako and eager for something more. By the 1980s, amid rainfall and despair, he joined thousands of expelled Tuaregs drifting into Algeria and Libya, where a diverse sort of revolution was brewing under Muammar Gaddafi’s ever-expanding camp.

As a report in WSJ information, Ghali received martial training and shortly emerged not just as a warrior, but as a charismatic leader in the Tuareg reason. But this insurgent had music. In the refugee camps, he gravitated toward a motley group of musicians who called themselves Taghreft Tinariwen — the” Radio of the Desert”. Armed with electric guitars and the writing of rebellion, Tinariwen gave the Tuaregs a fresh speech: music.

Ghali saw their possibility and backed them, supplying equipment and practice areas. He also contributed lyrics and drumming— certainly with drums, but with metallic jerrycans. This was revolution with a song. The team would go on to win a Grammy and sing with the likes of Bono and Robert Plant. Their patron, however, had other ideas.

In 1990, Ghali led a fresh Tuareg rebellion, signing a peace in 1991 after first profits. He emerged as the face of the revolution, also representing the Tuaregs at peace talks. But after the weapons fell silent and his own soldiers faded into government work or human life, Ghali stood at a crossroads. The earth was applauding Tinariwen. He had helped them increase. But what about his trend?

From Rebellion to Religion: A Fundamentalist Change

In northwestern Mali, in the late 1990s, a group of white-robed Muslim preachers arrived from the TablighiJama’at. They weren’t carrying weapons, but their ideology was dangerous. Their message: forego the pleasures of this globe, submit to belief, and spread Islamic cleanliness. And miraculously, their thoughts found a house in the most unlikely of ears.

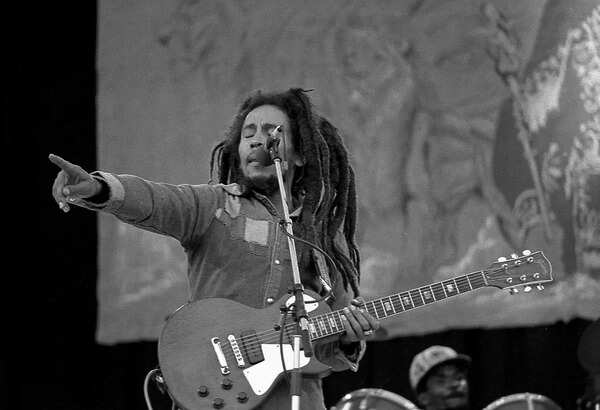

Ghali, when a nightclub-hopping chain-smoker who cranked Bob Marley in his vehicle, listened. Finally he changed.

Out went the liquor. In came the hair and the Quran. Companions were stunned. The person who once sang alongside Tinariwen then scolded them for drunkenness. He grew remote. By the 2000s, he was spending time in temples in Bamako and Paris, apparently brushing shoulders with secularists. Yet officials started whispering about his dramatic change.

When the Tuareg launched a new revolution in 2011, Ghali saw an entry. But this time, he wasn’t talking about Azawad. He was talking about Sharia. Rejected by the liberal MNLA for being too Islamic, Ghali formed his own party: Ansar Dine—” Supporters of the Faith”.

The harp had been replaced by the cannon.

The Rise of Ansar Dine and the Islamist Invasion of Mali

In 2012, as Tuareg and Islamist soldiers swept across north Mali, Ghali’s makes seized important places. Timbuktu, when the heartbeat of Saharan society, fell under Ansar Dine’s dark symbol.

Ghali wasted no time. Audio was banned. Instruments were destroyed. Ancient Sufi sanctuaries were smashed with hatchets. People were ordered home. Fornicators were stoned. The area became a futuristic problem wrapped in religious explanation.

France intervened in 2013, pushing the jihadists out of the places. But Ghali didn’t go away. He retreated to the Adrar des Ifoghas hills, regrouping for the next action.

JNIM: Coalition of Terror in the Sahel

In 2017, Ghali reemerged with a bigger plan. He merged several al-Qaeda-linked groups intoJama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin ( JNIM ) and declared himself its emir.

JNIM became a plague across the Sahel. Its soldiers launched lethal attacks on soldiers and civilians everywhere. They ambushed tankers, planted IEDs, and taxed whole villages. In pieces of Mali and Burkina Faso, JNIM became the de facto government — settling problems, collecting corn, and enforcing a twisted type of law and order.

Ghali, actually the planner, tried to model JNIM as the more “reasonable” militancy alternative to ISIS. But make no mistake: his soldiers also executed people, kidnapped ladies, and murdered those who resisted. In one especially terrible tragedy, they gunned over 600 people digging pits for defence.

Regional Fallout and International Answer

The panic sparked by Ghali’s conflict has toppled administrations. Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have all witnessed dictatorships since 2020, with autocrats claiming they only can stop the terrorists. In fact, their plans often play into Ghali’s arms.

The French were kicked out. The UN was sent packaging. In their position came Russian soldiers from Wagner, whose cruelty has turned visitors further against state forces. Ghali, seeing the reaction, has positioned himself as a protector of the people — all while orchestrating assaults and extorting areas.

He is now in his eighties, a wanted person with an ICC imprisonment permit over his head. Yet he remains completely, his soldiers entrenched, his reach growing. In the darkness of the Sahel, he continues to arrange problems while preaching devotion.

From Beats to Bloodshed

However, Tinariwen tours the world, playing to packed people in Boston, Berlin and Bamako. Their music speaks of longing and lost — sounds of a fantasy that once seemed within reach.

But the man who when clapped along beside them is nowadays a spirit in the mountains, a fugitive with blood on his hands. From plain rebel to separatists warlord, Iyad sa Ghali’s arc is both amazing and dreadful.

Again, he helped create the songs of liberty. Then, he silences them.