As Usha Vance stood beside her father, Vice President JD Vance, during his historic opening, she exuded calm assurance, her sari-clad appearance a vivid symbol of a changing America. But if you peered into the murkier edges of MAGA’s online ecosystem that morning, you’d find things much uglier than the opening festivities.

“Christ is King, not some filthy Indian hero, ” a MAGA-aligned critic snarled online. Another struck in with, “Will it be a cow in the White House quickly? ” These crude problems weren’t only casual trolling—they were a representation of a deeper pain with Usha Vance’s Hindu trust, a simmering resentment among sections of MAGA toward high-profile Indian-Americans who don’t fit the Christian nationalist casting.

It’s not only Usha. Vivek Ramaswamy, the biotech entrepreneur-turned-political flame, and Sriram Krishnan, the Silicon Valley techie then advising Trump on unnatural intelligence, have also been in the sights. Despite their plan position with MAGA’s cherished ideals—free marketplaces, technology, and an America-First approach—they remain strangers in the movements. Their evil? Being proudly Hindu, clearly American, and symbolizing a cultural America that MAGA’s key supporters fear is slipping aside.

Racist Problems Against Usha Vance

Usha Vance was born and raised in a Hindu home, embracing the religion’s abundant traditions and values.

Usha Vance, the second Indian-American Second Lady of the United States, epitomizes the expat success story that officials love to rally when it suits their stories. A Yale-educated lawyer and mother of three, she is a bible to America’s melting pot. But for MAGA’s more nationalist arms, Usha’s Hindu personality is a dark symbol.

“ I thought Vance was a Christian, ” read one post, dripping with pious anger, as if interracial marriage was the forerunner of the disaster. Others labeled her beliefs “pagan idolatry, ” turning centuries-old evangelical hostility toward Hinduism into a 21st-century meme war. Beneath the vitriol and disdain lies a broader discomfort: a worldview where non-Christian religions, especially one as artistically rich and morally democratic as Hinduism, are inexplicable and, consequently, threatening.

Popular Indian-Americans in Trump’s Remit

MAGA’s connection with Indian-Americans is, to put it politely, complicated. On one hand, Donald Trump has effectively elevated some high-profile desis into important positions, making them ministers of a different MAGA 2. 0. On the other hand, the nationalist undertone within MAGA usually bristles at their presence.

- Kash Patel, Trump’s dog in the fight against the so-called “deep state, ” has become a controversial number. Equal parts traditions warrior and monster, Patel’s aggressive approach to national security has made him a darling of MAGA’s extreme bottom, even as whispers about his identity dwell in the fringes.

- Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, the Stanford professor who loudly opposed COVID-19 lockdowns, has been embraced as the intellectual backbone of MAGA’s pandemic skepticism. He’s proof that desi academics can still dominate a debate when handed the mic.

- Sriram Krishnan, the Silicon Valley darling, was tapped to shape Trump’s AI policy—a sign of the administration ’s grudging acknowledgment that America’s future competitiveness hinges on talent, regardless of ancestry.

- Tulsi Gabbard, while not Indian-American, is a Hindu who often gets honorary desi status. Her appointment as Director of National Intelligence feels almost like a nod to MAGA’s internationalist ambitions, even as it makes the evangelical right queasy.

- Vivek Ramaswamy, MAGA’s golden child of economic policy, remains a paradox: a darling for his brash anti-woke rhetoric but suspect for his unapologetic Hinduism. He was recently dropped as co-lead of DOGE, making many wonder if his race played a part.

These figures underscore Trump’s calculated attempt to woo the Indian-American demographic—a group with outsized clout in technology, academia, and finance. But their inclusion also sparks fierce resistance among MAGA’s nativists, who view them as emblematic of an America they no longer recognize.

The Sriram Krishnan Controversy

When Trump appointed Sriram Krishnan as Senior Policy Advisor for Artificial Intelligence, the move was hailed as a victory for pragmatism—until Laura Loomer and her ilk showed up. The far-right commentator accused Krishnan of betraying Trump’s “America First ” ethos, claiming that his support for immigration reforms like removing country caps on green cards would disadvantage American workers.

“Another tech bro taking over America, ” sneered one tweet, weaponizing the model minority stereotype. MAGA’s digital trolls weren’t just attacking Krishnan’s policies—they were signaling their discomfort with his very presence. After all, nothing says “threat to white Christian dominance ” quite like a brown immigrant revolutionizing the way America leads in global AI innovation.

Vivek Ramaswamy and the Limits of Inclusion

If MAGA were a frat, Vivek Ramaswamy would be the overachieving pledge who parties harder than the brothers and aces every exam, yet still gets left out of the group photo. Ramaswamy’s commitment to free markets and his sharp critiques of woke ideology make him a natural fit for MAGA, but his Hindu identity complicates things. Evangelical Christians, a core MAGA constituency, view Hinduism with deep skepticism. Ramaswamy’s references to the Bhagavad Gita have been criticized as relativistic—a dangerous departure from the evangelical insistence on biblical exclusivity. He’s the perfect candidate on paper, but in practice, his unapologetic Hinduism and Indian heritage keep him at arm’s length.

The Pagan Problem

At the heart of MAGA’s discomfort with figures like Usha Vance, Vivek Ramaswamy, and Sriram Krishnan lies what some evangelical leaders have long referred to as “The Pagan Problem. ” Hinduism, with its polytheistic traditions, vibrant rituals, and richly symbolic deities like Ganesha and Kali, has historically been framed by Christian conservatives as idolatrous and antithetical to Western values. This narrative, rooted in colonial-era missionary rhetoric, still permeates parts of the MAGA movement. For evangelical Christians, who form a significant portion of MAGA’s base, the visual and philosophical differences of Hinduism evoke suspicion and alienation. These deep-seated biases fuel the movement ’s broader struggle to embrace Indian-Americans who refuse to downplay their heritage or faith, viewing them instead as symbols of an increasingly pluralistic America they fear losing control over.

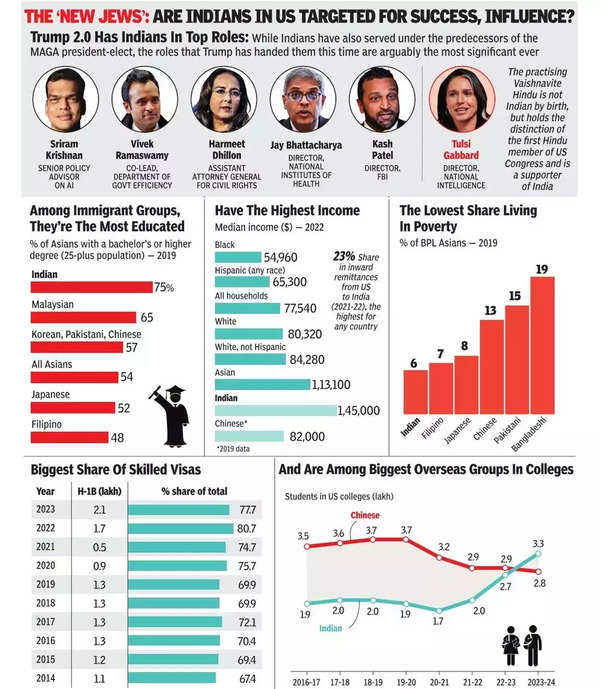

Are Indian-Americans the New Jews of America?

Indian-Americans are increasingly drawing comparisons to Jewish-Americans of the 20th century: influential, successful, and often resented. “Our clout comes from the fact that the Indian community constitutes what I call the ‘next Jews ’ of America, ” said Prof. Jagdish Bhagwati in 2000, and his words have only grown more prescient.

Indian-Americans are the highest-earning and most educated ethnic group in the US. Their dominance in Silicon Valley—Sundar Pichai ( Google ), Satya Nadella ( Microsoft ), Arvind Krishna ( IBM )—and leadership in academia, medicine, and politics mirror the Jewish-American ascent in earlier decades. But with success comes envy and suspicion, particularly in an era of economic insecurity and resurgent nationalism.

Admiration and Resentment: The Duality of Success

Indian-Americans embody the American Dream, but that dream comes with a price. Just as Jewish-Americans faced accusations of wielding too much influence, Indian-Americans now navigate similar waters. MAGA, for all its professed meritocratic values, struggles to reconcile its admiration for their achievements with a visceral resentment of their visibility and cultural distinctiveness. MAGA’s relationship with figures like Usha Vance, Sriram Krishnan, and Vivek Ramaswamy exposes its identity crisis. The movement wants to project an image of inclusion and modernity but remains tethered to a foundation of Christian nationalism and ethnocentrism.